“Space Junk,” by John Berkey, a 1979 Life Magazine illustration.

This email isn’t really a full-blown review of the 2003 art collection The Art of John Berkey, by Jane Frank. Instead, I’ve included most of my notes from the book, which will be the backbone for what will turn into my entry in my own art book on retro sci-fi.

The review: It’s a good book! Smart analysis of a big figure in sci-fi art. I’d expect nothing less from Frank, who did a series of retro sci-fi art books in the 2000s for the publisher Paper Tiger (I’ve previously covered The Art of Richard Powers).

This book helped me put my finger on why Berkey is so influential: He helped late 60s/early 70s sci-fi form a distinct visual image of itself by using Impressionism. The soft brushstrokes of American Impressionism naturally create a nostalgia when the subject matter is the past, and that translates to a similarly rose-colored idealism when the subject is the future. Which was perfect for a genre that was trying to get a little distance from its pulpy history.

Here are the notes, which are a mish-mash of direct quotes from Berkey or Frank along with a few of my rewritten summaries of Frank’s analysis.

***

Page 11: Berkey on his reputation as a space and science fiction artist: “I was surprised how quickly an artist can become known for a certain kind of work.”

***

Page 12: Space art is tough: There is no linear perspective, so relative size needs to stand in for it. Overlapping objects helps with that, but artists need to find other ways to signify scale. Here’s Berkey’s bag of tricks:

“As for spacecraft, it seemed logical that they would have to look like they could fly and go fast. A triangle looks more like speed than a rectangle. Familar elements like windows can give the illusion of size. For some reason, the more successful paintings always seemed to have the viewer looking up at the craft. We will always think of space as up until the day it becomes out.”

Here’s the image that best illustrates how Berkey does scale, “Leaving,” a personal work from 1998. Which feels larger, the triangular ship on the lower right, or the egg-shaped, window-packed space station in the center of the frame?

***

Page 16: Berkey, on the (lack of) differences between illustration and fine art: “In the music world there are ‘pianists’ and ‘piano-players,’ all of whom play the piano.”

***

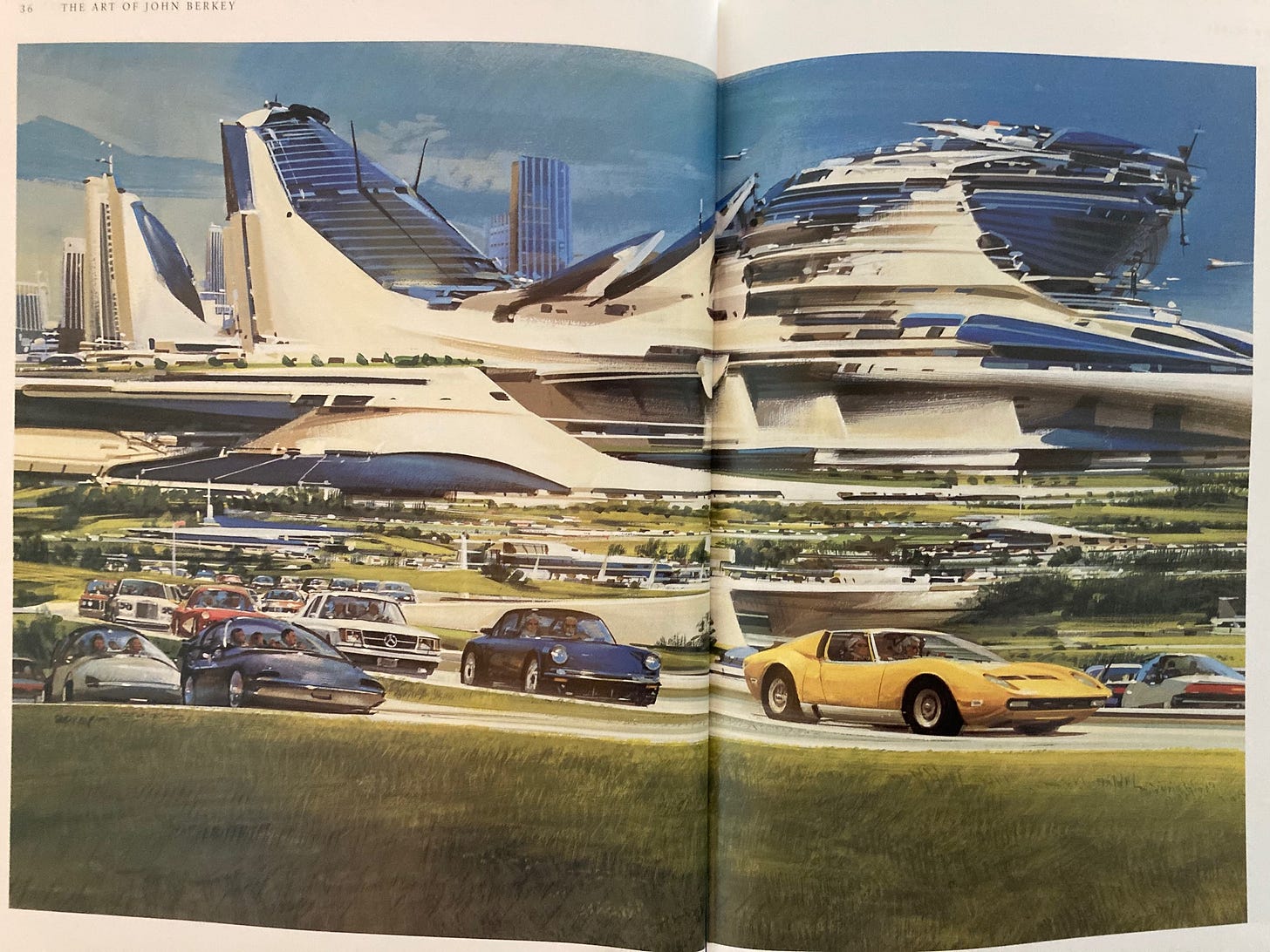

“Antique Car Rally in the Year 2040,” 1983, for Road and Track magazine:

Jane Frank says the mid-50s were a turning point between the science fiction genre’s “rough beginnings” and “the genre’s true flowering” — granted, that’s a big simplification! But it was a big shift for the genre, and figuring out how to describe it has been a big challenge for me with my book.

***

Here’s my own summary of Berkey’s early career, drawn from the book:

The unassuming Midwesterner spent eight early-career years at Brown & Bigelow, the world’s largest commercial calendar publisher. He’s in good company — Norman Rockwell had previously worked there, too. Berkey’s Impressionist style was a perfect match for American calendars, serving up sleigh rides and oil rigs with a nostalgia-shaded authenticity that never tipped over into the saccharine.

Then, when he shifted to sci-fi in the late 60s, that same idealistic authenticity was exactly what magazines and publishers needed to legitimize their science fact and science fiction, helping to set it apart from the genre’s pulpier reputation from earlier decades.

***

Here’s his first sci-fi novel cover, for Robert Heinlein’s Starman Jones. He used himself as a model.

Frank groups Berkey’s sci-fi art into three buckets: Narrative/storytelling (Starman Jones is an example); conceptual (like a still life of a bowl of fruit, but with a spaceship); and futuristic Impressionist (shapeships too abstract to count as conceptual).

Here’s “Space Walker,” 1985, one of the abstract ones:

Another abstract one, “Dive and Attack,” personal work, 1979:

Page 48: Berkey thought illustrators’ numbers were dwindling: “Some [illustrators] have passed on and none have taken their place. The field of illustration has suffered from all the changes related to the computer.”

Page 49: Berkey: “One of the things I enjoy about science fiction or any art of the future: the client may not like it for any of a number of reasons, but never because it’s wrong.”

***

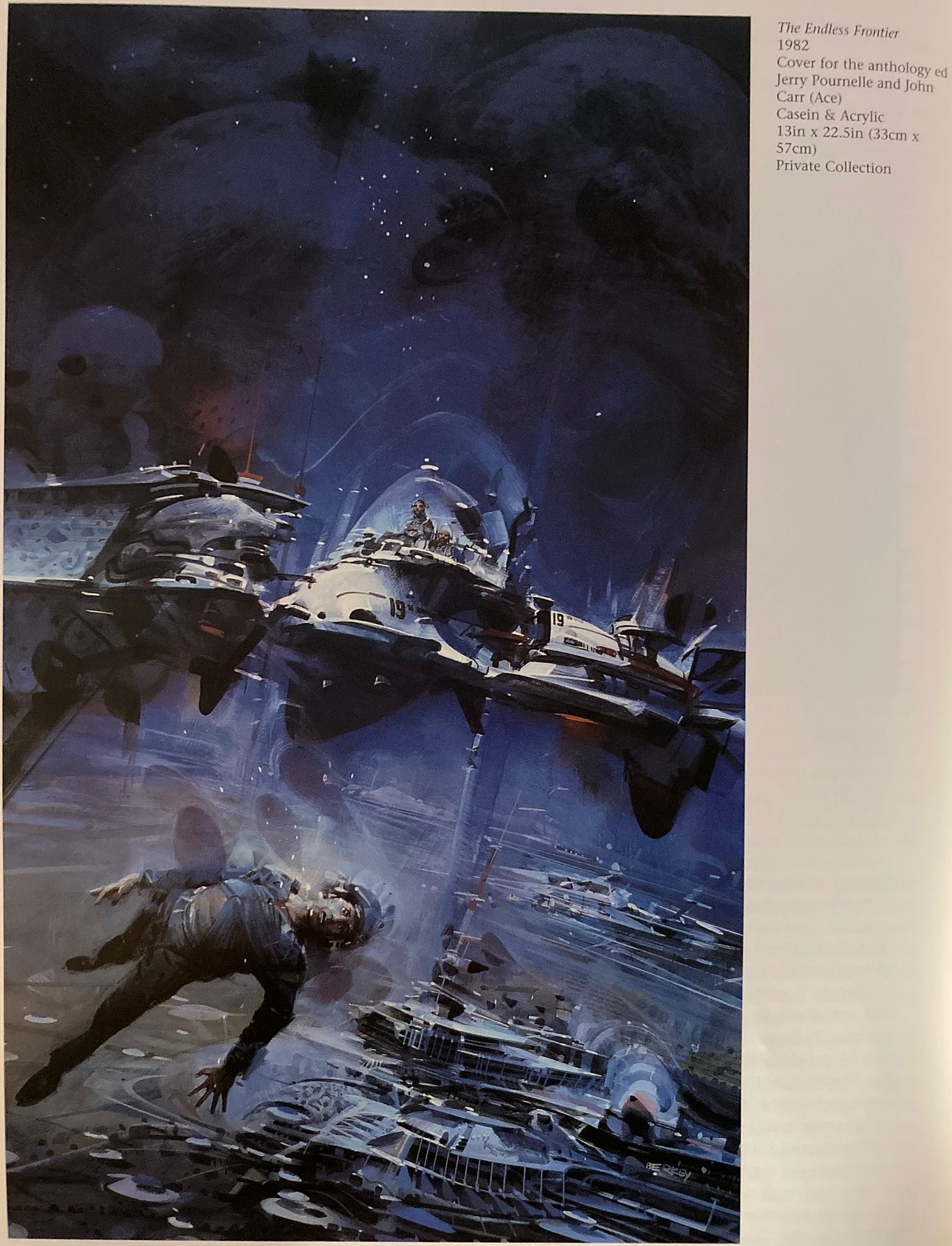

1982 cover to The Endless Frontier:

Here’s a weird one from 1978, a personal work called “Astronaut in a Harem.”

***

Berkey also threw in a few comments that weren’t quite as related to his work and career a little later in the book — I suspect he may have been running out of things to say: